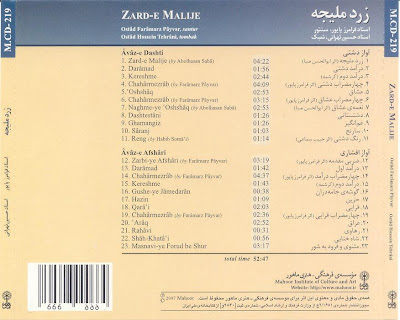

âvâz-e dashti

01. Zard-e Malije

02. Daramad Dashti

03. Daramad Dovom

04. Chaharmezrab Dashti

05. Oshagh

06. Chaharmezrab Oshagh

07. Naghme Oshagh

08. Dashtestani

09. Gham Angiz

10. Sarenj

11. Reng dashti

12. Zarbi Moghadameh

âvâz-e afshâri

13. Daramad Aval

14. Chaharmezran Daramad

15. Daramad Dovom

16. Gooshe Jamedaran

17. Hazin

18. Gharaei

19. Chaharmezrab Gharaei

20. Araq

21. Rahavi

22. Shah Khataei

23. Masnavi Va Foroud Be Shur

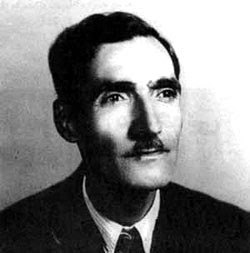

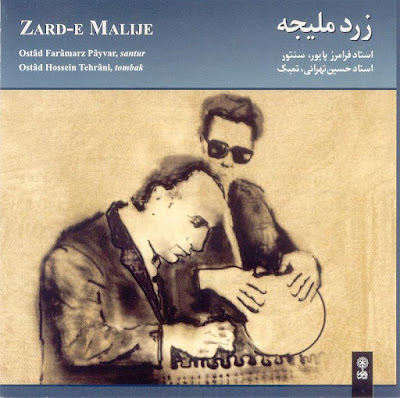

فرامرز پایور Farâmarz Pâyvar [1933 - 2009, Tehran] was an Iranian virtuoso of the santur, a 72-stringed hammered dulcimer. He was born into an aristocratic family of artists. His father, Ali Pâyvar, was a painter & professor of French at the University of Tehran. Both his father and grandfather played santur & violin, & were associated with the great musicians of their eras. Pâyvar’s mother was also interested in the arts in general & musique in particular. She was aware of her son’s talent and encouraged him to play the instrument.

At the tender age of 17, Pâyvar began his musical career by studying with renowned Iranian musician Abolhassan Saba [1902-1957]. He studied the Radif repertory & played the santur with Saba for eight years before he graduated from his mastership class & was able to play alongside his teacher Abolhassan Saba on Iranian National Radio.

Pâyvar was highly skilled on the santur and soon became very famous. After Saba’s death he began to study with four other masters: Nur-Ali Borumand, Rokneddin Mokhtari, Abdollah Davami, and Haji Aqa Mohammad Irani.

In 1958, Payvar began teaching the santur at the National Music Conservatory. Although once perceived as marginal, the santur is now considered an important solo instrument in Persian classical musique, largely as a result of his work. Over the course of his career, Pâyvar revolutionised its playing, led two major ensembles and made numerous recordings.

He also published several books on practical and theoretical aspects of Iranian classical musique. These included a series of influential guides on how to play the santur, & a popular manual for the tar, a long-necked lute said to embody the spirit of Iranian musique.

Pâyvar was renowned for his strict personal discipline and demanded the same of his students as well as members of his ensembles. This meant that their line-ups hardly altered at all, in contrast with the volatile changes that affected other contemporary Persian groups.

He founded his own school of performance for the santur, with a novel emphasis on arpeggiated figures reflecting an openness to 'Western' influence. Another innovation that caused controversy among some traditionalists was his use of felt on the hammers used to strike the instrument's strings. This resulted in a softer, less metallic tone that was suggestive of the piano – itself thought to have been derived from the santur.

Before the 1979 Iranian Revolution, & after the end of the Iran-Iraq war, Pâyvar travelled internationally as a cultural ambassador for Persian musique, performing in North America, Britain, Europe, various Soviet Republics and Japan. During the 1960s and 1970s he recorded a number of albums for French labels. We may remember his legacy through his many peerless recordings. r.i.p. Farâmarz Pâyvar 1933 - 2009

حسین تهرانی Hossein Tehrâni [1912 – February 25, 1974] was the most influential tombak player of the 20th century. Born in 1912 in Tehran [where else?] he began his studies at a time when tombak playing was regarded not as a respected music career for the player. "When I began to play tombak, the instrument was a humiliated one & according to general consensus it was only suited for low-class musicians," he once said. From 1928 he went to study tombak with Hossein Esmailzadeh, himself a master kamanche player. Since modern musical notation was not common during those days, he used mnemonic devices to memorize rhythmic patterns.

He single-handedly is responsible for the high stature attained nowadays by tombak, through his originality of musicianship and due to his generous personality. He also formed a tombak ensemble to encourage young players to play in group and with large orchestras. To provide them with a performing repertory he also composed fantastic pieces for the ensemble. He died in 1973 after a long period of illness. May his memory will be cherished forever. r.i.p. Hossein Tehrâni 1912 – 1974

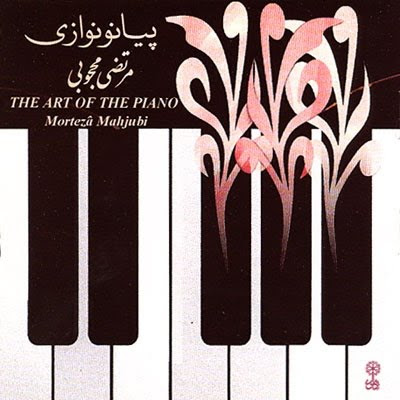

someone fond of the Mortezā Mahjubi recordings inquired about a good santur joint & this is one i spin frequently. one can readily hear the masters' felt on the hammers technique resulting in resonances not unlike some alien iranian piano, complimented by some encroyable tombak accompaniment. my guess is that these recordings were made in the 60's. 320 thanks to Ambrose Bierce for illumination & stellar sounds. حفاری عمیق تر