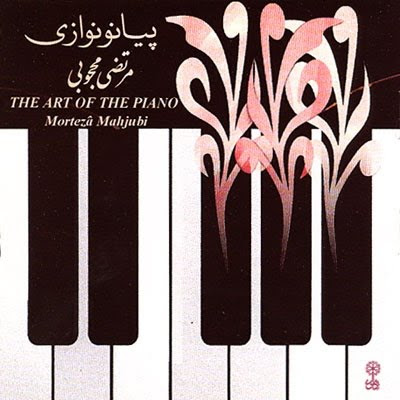

1 dastgahe se gah دستگاه سه گاه

2 dastgahe homayoon دستگاه همایون

3 bayate tork بیات ترک

4 avaze dashti آواز دشتی

5 avaze aboo ata آواز ابو عطا

6 avaze afshari آواز افشاری

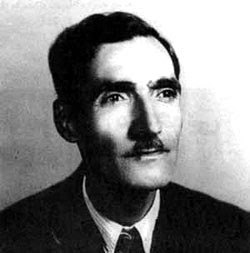

Mortezā Mahjoubi مرتضی محجوبی [Tehran, 1900 - 1965] was an innovative, largely self-educated composer & performer who was renowned for his masterful utilization of the piano in performing traditional Iranian musique. Mortezā came from a musical family; his father, Abbas Ali Mahjoubi, played the ney, the Persian wooden flute; his mother, Fakhressadat, could play a little piano & his brother, Reza Mahjoubi, became a great violinist. Morteza's family happened to own a piano, a rare possession among people of Tehran during that time.

This very suitable family atmosphere & his own natural genius helped Morteżā to get initiated into the world of musique in his early childhood. As a child, he often sat behind the piano & played this instrument in his own childish fashion, creating certain tunes. His parents, noticing his aptitude for musique, took him to Ḥosayn Hangāfarin, a famous musician & performer of violin & piano to teach him the basics of musique & performance of the piano. They later sent him to Maḥmud Mofaḵḵam, a pianist & outstanding student of master musician Āqā Ḥosaynqoli, to further familiarize him with the repertoire [radif] and melody sections [guša] of traditional Persian musique & to aid him in mastering the art of piano playing.

Maḥjubi’s genius in absorbing musique manifested itself from early childhood. By the time he was ten years old, he had become an expert pianist who played in the gatherings of the aristocracy. His fame as a child prodigy reached such proportions that he, at the age of ten, participated in a concert featuring ʿĀref Qazvini & accompanied ʿĀref’s singing on the piano. Since ʿĀref was extremely fastidious in regard to the performance of his band’s members, his acceptance of a young boy as his own back-up performer illustrates Maḥjubi’s masterful excellence as a youthful pianist. He had become a well-known musician by the age of twelve and was regarded, by many, as the leading piano performer of his thyme.

Maḥjubi was not familiar with the international system of musical notation, so he invented his own system of writing music by using symbols that were somewhat similar to the siāq script (a system of signs once used in accounting. Parviz Yāḥaqqi, the Persian composer and violinist, has related that he had once composed a song that was to be broadcast on the radio. When the musical note sheets were distributed to the members of the orchestra, Maḥjubi asked Yāḥaqqi to play the song on the violin. He then jotted the tune down in his own style of writing music on the back of his cigarette pack. When the rehearsal started, Maḥjubi’s performance was unexpectedly more accurate than the rest of the orchestra.

After the establishment of the Radio Tehran, Maḥjubi was one of the first musicians to join & take part in its musical programs. Later, in 1956, when radio program entitled Golhā was launched, Maḥjubi became one of the most outstanding figures of this musical program, which aimed at demonstrating the aesthetic relationship between poetry and music in Persian culture. According to those present, Maḥjubi would sometimes go to the Golhā studio at Radio Tehran without an appointment or an advanced notice and play the piano in solitude. On such occasions, the technical personnel of the Golhā program would, without Maḥjubi’s knowledge, record his performance on tape. These recordings are now considered among the treasures of traditional Persian musique.

The significance of Maḥjoubi’s work is partly in the fact that he performed Persian melodies on a completely Western instrument with such masterful excellence that one would think the piano was truly a Persian instrument. Maḥjubi’s melodies & style contain embellishments and accents that brilliantly manifest genuine characteristics of Persian musique.

Maḥjubi was one of the most prominent improvising music performers. He always began playing without advanced planning and his works always took form under the influence of his feelings and his sentimental impressions at the time of playing the piano. For this reason, if he played in the Dašti mode ten different times, ten very different works would be created. Due to this style of work, none of his compositions resemble any other.

On a related 'note', further precious pianoriental recordings from Mortezā were subsequently dropped here & an lp by one of his contemporaries, iranian pianist Javad Ma'roufi, were recently unfurled by the resplendant ghostcapital